| Taking Stock of William Jennings Holman and His Improbable Locomotive, Part 3 |

Preface / Table of Contents Part 4: The Occasional Sourdough: |

|||||||

|

Fort Wayne & Southern Rail Road |

||||||||

| Beyond being Holman's only successful enterprise, Peru & Indianapolis turned out to be wonderful schooling for his future string of shabby activities. He came to understand the intricacies of railroad finance and its potential for lavishly lining promoters' pockets - given the proper setup, of course. Fort Wayne & Southern Rail Road provided him the opporortunity to hone and take advantage of these skills with some post-graduate work.

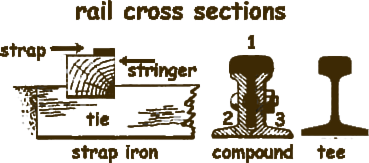

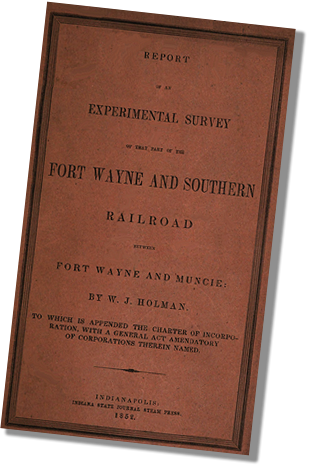

FW&S was one of those paper railroads that never managed to lay a rail. Its founders created the company with the noblest of intentions, or at least it convinced investors that this was the case, for during the company's existence, it managed to raise a considerable amount of money from them, yet it perpetually was broke. Where (or more accurately, to whom) the money went is an ongoing mystery, because after several years of existence, the company had only managed to turn over a few shovelfuls of earth. FW&S showed clear signs that it was a classic case of fraud long before Holman jumped aboard and made it worse. The company's irregularities actually dated to its first day of its existence, January 15, 1849, when the Indiana state legislature granted it a special charter to form a railroad corporation. Granting a charter is one thing, but under state law, it had to be formally accepted by the grantee in order for it to go into effect. This, the company founders, including Joseph Holman, failed to comprehend. Instead, they blithely proceeded forward buying up land and selling stock without official sanction. It was not until early 1852 that the "pretend railroad", as a judge later labeled it, even got around to conducting a survey between its contemplated end points, Fort Wayne and Muncie. With Joseph holding a spot on the (illegitimate) board, it was inevitable that his son would gain the contract to perform the task, on which W.J. began work in late March. When he was done, W. J. submitted his Report of the Experimental Survey of That Part of the Fort Wayne & Southern Railroad Between Fort Wayne and Muncie to President William Rockhill, a man whom he would eventually replace. He at length described his suggested route as essentially straight and relatively flat, with only a few bridges over minor water courses. According to his computations, the total cost for preparing the right of way and laying track would be exactly $388,397.70 if flat-bar-topped wooden rail was adopted, or $574,498.28 if compound rail was used. Rail types under consideration for FW&S: Note that the three-part compound rail shown was typical of its class, but Holman's various permutations over the years (covered in Part 6) were far from typical. The (in the above case, three) individual lengths were joined in staggered fashion, thus eliminating the tendency of tee rail butt joint bolts to work loose, causing the rail ends to sag. Gradually, improved cross sections for tee rail and its connecting "splice plates" (aka 'angle bars") mitigated much of the issue and compound rail's main advantage. "Tee" rail Holman dismissed out of hand, even though it was already the industry standard; hands-down better than strap iron rail and much less expensive than compound rail. Holman did not see it that way. By then he had already embraced a life-long conviction that compound rail was superior to all other forms, but railroads for the most part had already rejected compound rail because its multi-part construction had proved to be more expensive to purchase and maintain than tee rail. Conceivably, he was already far enough along in the design of his own novel variation (which resulted in an 1855 patent, as we shall see later)that he held an outside hope of landing a contract to supply rail. Otherwise, the precision of his down-to-the-penny estimates were peculiar enough, and should have raised a few eyebrows, but Holman made the presentation even less credible by tacking on a passage of circumlocutious inexactitude that at most had marginal relevance to his survey:

It seems appropriate that Holman's prose reads like an entry to the Bulwer Litton Fiction Contest, since his "estimate" was only so much hot air, but such impervious language was expected of men of learning. FW&S's promoters loved the report and welcomed it with open arms, especially since as backwoods railroad amateurs, they were in no real position to do otherwise. They simply were not equipped to question the figures of an "experienced" railroad engineer who delivered his findings with such labyrinthine panache. |

||||||||

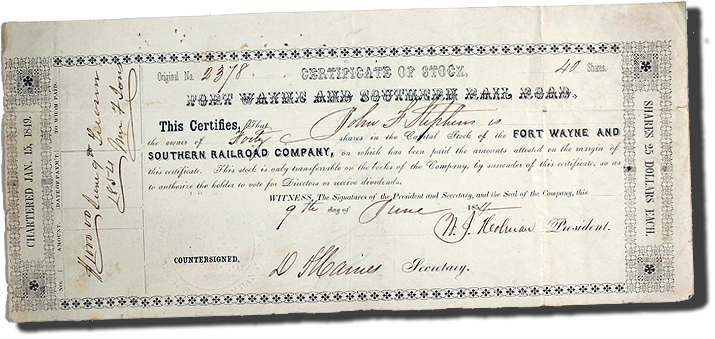

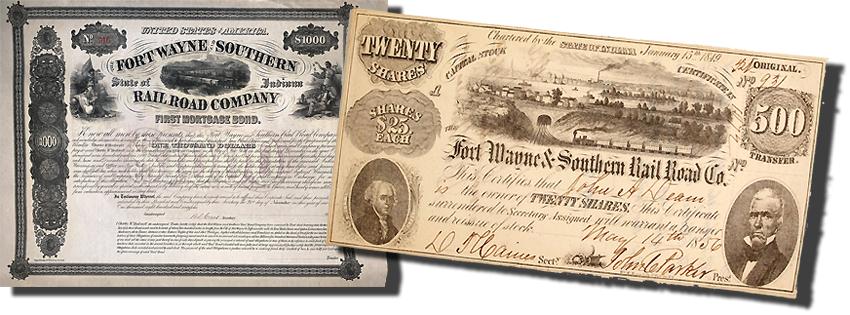

| At right is an 1854 version of a FW&S stock certificate, signed by President W. J. Holman and the ever-present Secretary David Haines. |

|

|||||||

|

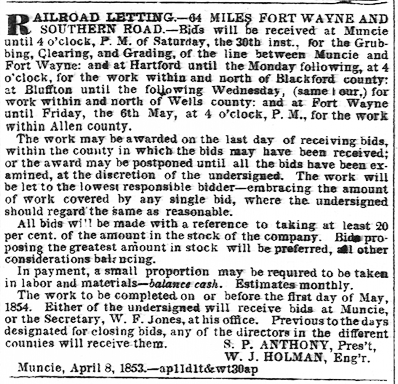

With Holman's rough survey in hand, company agents proceeded to acquire real estate for right-of-way, both through purchase and contributions. A full year passed before contracts were let out for right-of-way work in April 1853, but these were confined to limited grubbing and grading on a few disconnected sections. Bidders were required to take at least 20% of their payment in stock and in addition "a small proportion may be required to be taken in labor and materials - balance cash. Estimates monthly." The proposed contract terms (see image) made the financial situation clear. The company was land rich, but cash poor, and could not afford to pay contractors outright. Several circumstances may have figured into this, including a current economic downturn in Indiana, and a sudden explosion of paper railroad, as well as a fair number of legitimate ones, that severely diluted FW&S's ability to attract investors. Many years later, a very plausible, but unsubstantiated, alternate explanation surfaced from a critic of the company's machinations, who claimed that once the company had secured most of its right-of way, it turned around and mortgaged it for $2.5 million in bonds. This was normal practice, but the implication was that, rather than apply the money towards construction, company officers instead used it to line their pockets. If this was the case, some of the proceeds from future fundraising efforts necessarily would have gone towards servicing this debt and to the further lining of pockets, leaving a meagre remaining balance to fund a ruse of construction. The credence of the claim is questionable, since in late 1854 Holman publically claimed that FW&S so far had taken on no bond encumbrance whatsoever on either its road or real estate. Plenty of bond sales and manipulation filled in the company's later days, however. |

|

|||||||

|

|

|

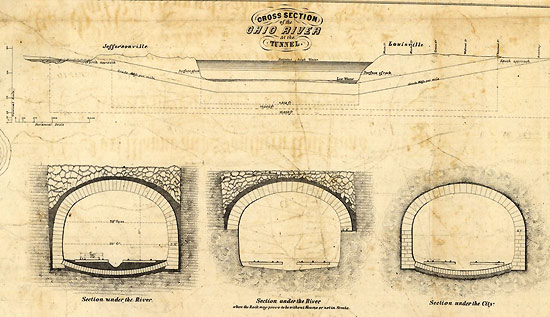

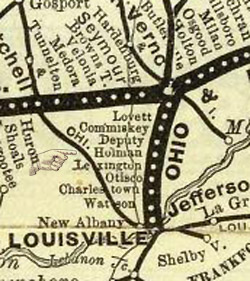

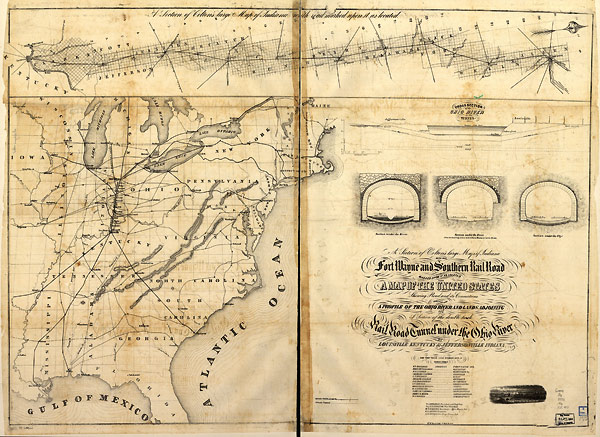

Even if the rumor of onerous bond debt was false, FW&S's homely aim to connect two towns whose sum total population was less than 5,000 was not the stuff to attract a horde of investors. Originally, the railroad's founders had contemplated building much further, all the way to the Ohio River. They concluded that a project of such scope was beyond their present means, but the idea never really left the table, so they were well-primed when Holman re-entered the picture in July with a plan to extend the line 68 miles further south from Muncie to Jeffersonville across the Falls of the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. He laid out his ideas to the board in a lengthy, nearly impenetrable written discourse that dwelled upon the advantages of more numerous railroad connections, which would more than justify the cost of the 162 mile railroad, which he now figured at $3 million, a steep per mile increase over his estimates of a year earlier. Although he made no reference to a direct Louisville connection, he nevertheless felt it incumbent upon the city fathers to ante up $300,000 to help the railroad along. Again, his plans were well received by the board, so much so that his work put him on the fast track to election to the company presidency in October. What cinched his election was a grand new plan that he had been privately circulating to advance the railroad to Louisville to connect with southern railroads. A bridge between Jeffersonville and Louisville would have made a lot of sense, but this was too conventional to suit Holman. He wanted to do something that would make a splash, and more importantly, make him stand out, so he conjured up a proposal to tunnel under the river immediately above the Falls of the Ohio that lay between the two towns. He was utterly convinced that this could be done with great economy by using cofferdams and the drop of the falls to steer the waters away from what was not so much a tunnel as a ditch with a roof that sat barely below river bottom. From end to end, it would measure exactly 4313 feet. Including the approaches at either end (true tunnels that would carry the line under the more populated areas of Louisville and Jeffersonville) plus the open cuts leading to them, the whole thing was to be 13, 650 feet, or 2.6 miles long. That would have been a lot of digging, but Holman assured everyone that it would be cheaper than a bridge. Initially, nobody disputed that. |

||||||

| In early March, 1854, the Kentucky legislature gave its official blessing to the project with a charter to go "through, into, over and under" (quote from Tunnel 4 Southern) its territory to make a connection with the Louisville & Nashville and Louisville and Memphis (later, L&N) railroads. Louisville's board of aldermen signed-off on the plan in May, and in addition absolved the railway of future taxation. Shortly afterward, Holman and H.R. Weeks, an engineer from Vernon, Indiana, unfolded the details to the public in a 48 page pamphlet deemed the Exhibit of Condition, Resources and Prospective Business of the Fort Wayne and Southern Railroad: together with cost by contract and estimate of main line, and tunnel under the Ohio River at Louisville. (A safe surmise is that Holman was responsible for the title.) On the 29th, staunch supporter Louisville Daily Courier published a letter from Weeks to the FW&S board that summarized details, along with an editorial gushing with praise for Holman's "energy" and Week's "competency". Harvey Russell Weeks was a 25 year old farmer who, over the years, engaged in surveying to supplant his income.

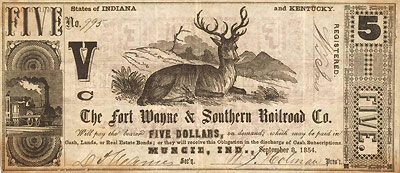

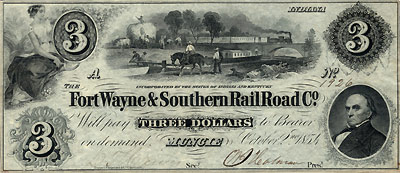

This was a heady moment for Holman and his associates. Sadly for them, the politicians' enthusiasm stopped short of opening the public coffers, and stock sales proceeds continued to be disappointing throughout summer. FW&S had accumulated well over a million dollars in subscriptions by this point, but this amount was deceiving because of the easy purchase terms, a low down payment with four years to pay off the balance. Given Holman's claim later in the year that the company held no bond debt, it is curious that they did not then commence mortgaging their real estate, for it was the only thing of value that the company owned. During this time of distress, when FW&S was so pressed for money that Holman may have been forced to drink mere mid-shelf wine, the men came up with a dandy alternative to bonds that was a much more straightforward way of raising cash. They began printing their own money. Such a thing was legal during the Free Banking Era of the 1830's to 1860's, when Federal specie and currency was hard to come by in remote developing regions of the United States such as Indiana. By way of solution, Congress granted banks and railroad companies the right to print their own currency with the general proviso that they were sufficiently backed to allow note holders to redeem them on demand. This led to a proliferation of what were called Wildcat Banks, chartered and regulated by state legislatures, rather than the Federal Government. Oversight and enforcement of the wildcats therefore varied by state, and in Indiana's case, there essentially was none. Villans could not have been more pleased with the arrangement. Money for nothing was the perfect solution to FW&S's dire straits. |

||||||||

|

left, Fort Wayne & Southern notes - The September, 1854 first issue appeared on thin, cheap paper (note the backside bleeding through), causing so much mockery that a more substantial-looking series of notes came out the next month. That appears to be Daniel Webster stiffly staring at us from the second series $3 shinplaster. The railroad's selection of images might have been better. The elk looks half asleep, while Webster had been dead for two years. right: This letter to the editor of the Evansville Daily Journal points out the limited circulation of shinplaster lists and "counterfit detectors". By the date of this query, FW&S as a functioning organization had been dead for more than a year, yet the notes continued to turn up on fraud lists at least though 1858. |

|

||||||

The public caught on pretty fast, and wise people shied away from private currency unless it was unavoidable. "Shinplasters" they called them, because that was about all that they were good for. FW&S began issuing its own notes in $1, $3 and $5 denomonations bearing Holman's signature in September, 1854. To their dismay, contractors and other debt holders suddenly found themselves being paid off in notes that resembled cheap-looking raffle tickets. In truth, it would have been like winning a raffle to exchange them for cold, hard genuine U.S.cash, for according to the terms on the their faces, anyone holding a note could exchange it at the FW&S main office, BUT the company reserved the option to give cash, land or real estate bonds in trade, as it saw fit. (Note again that Holman three months later claimed no bond debt.) A few days after their shinplasters appeared, the Louisville Journal implored the public "to be on their guard" over the "miserable lithographs", which appeared to be exactly as they were, freelance junk unsanctioned by Indiana or Kentucky legislative charter. (Intriguingly, the face side of original series implied official blessing from both states on its face, but succeeding runs only named Indiana.) Indeed, the shinplasters made such a bad impression that within a month printers began churning out an improved edition, replete with high quality engravings of jaundiced old men (Daniel Webster?)whose scowls better conveyed conservative substantiality than the fatigued-looking elk of the first series. During a December holidays state of affairs message in the Louisville Journal, Holman squiggled around questions of authenticity by maintaining that the "notes are pronounced a legal issue by councel of unquestioned ability", adding that they were "always redeemable from such means as the company may have." These were not words that instilled confidence to one reading between the lines. At about the same time, FW&S's notes began to occupy positions on newspaper shinplaster lists and "counterfeit detector" publications, but these alerts lacked anything near universal distribution. As a figurative homage to wild west style laissez faire capitalism, the phony notes continued to circulate unabated by the authorities for several years after FW&S effectively folded up shop.(see box above) |

||||||||

|

Perhaps FW&S's most noteworthy achievement was The Map (author's appelation), produced under the guidance of W.J. Holman. Within it is a precise, down-to-the-section-lines drawing depicting the proposed route, which must have surprized some land owners in areas where the future right-of-way location was still a bit fuzzy. Otherwise, the railroad's central place in the universe is quite evident. Note that it debuted in October, 1854 to cover the year ending in October, 1855. The tunnel cross sections are enlarged below. An online high resolution copy of The Map is available at Library of Congress. Also noteworthy is how the map has come to help support a present day cottage industry that prints up copies of LC maps for sale on Amazon and eBay. | |||||||

For an essentially 'paper' railroad only marginally defaced by construction, FW&S's highly attractive second edition of shinplasters rightfully might have represented its defining achievement had it not been for Holman's concurrent masterpiece, The Map. If it was not for Library of Congress's thoughtful preservation and digitization of The Map, we would not comprehend FW&S's contemplated position in the universe, nor could we fully visualize how Holman planned to pull off the tunnel. (Note under map about EBay and Amazon cottage industry) It truly is a wonderful document, whose only shortfall is that it failed to do its intended job, loosen money belts. The Tunnel The idea of tunneling under a river using pick and shovel knowhow of the 1850's seems a little far-fetched today, especially when we consider that the first subaqueous railroad tunnel in North America, under the St. Clair River between Michigan and Ontario, did not open until 1891, and it employed several new technologies that were invented on the fly. But we are talking Western Hemisphere here. The Brits already had managed to dig *one* tunnel under a river, below the Thames in London, but it took three and one-half decades of trying. Richard Trevethik, the versatile Cornish mining engineer, took the first go at it in 1807, three years after producing his best known work, the world's first railroad steam locomotive. Early in the second year of tunneling, when the bore was within 140 feet of the far bank, the flooding began. A second flood sunk the project's finances, causing Trevethik's return to tinkering with steam locomotives before sailing towards a series of mining and exploring adventures in South and Central America, one involving a hitch in Simon Bolivar's army. Trevethik's basic failing was that he had not invented the tunneling shield, a device that limited water infiltration and cave-ins to acceptable levels during excavation. This was left to Marc Brunel, a prolific inventor in his own right, who had made quite a name for himself as an engineer after fleeing the French Revolution. Using his patented shield, he and his son began their own sub-Thames attempt in 1825, only to discover that his device was not as fool proof as they thought. As with Trevethik, floods caused funds to dry up, and work did not resume for seven years. Then, their amazing accomplishment took another decade to finish. It opened for roadway traffic in 1843, but in short time was converted to railway use. The London Overground still runs through it. |

||||||||

| The tunnel cross sections at top left from The Map (click on the image for a larger one) give us indications that Holman was out of his engineering depth when he designed it, and may have intended the drawings to be nothing more than something that looked good on paper. He envisioned locating it just above the Falls of the Ohio, where he figured it would be easy to divert the river away from the work via coffer dams. Except where he would be forced to bore through solid rock, Holman intended to build a giant doubletrack trench, line it with cut stone, seal it with "natural cement" that he expected to find in the ditching process, then finally cover everything with rock and gravel about three feet deep.

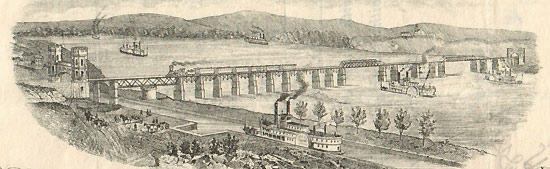

Holman's engineering experience came from canal building, where leakage was more of an annoyance than a danger. Conversely, a major leak in a tunnel could spell disaster - just ask Trevethik - and even a minor one could pose major problems. What Holman overlooked entirely is that the gravel river bottom at The Falls would continuously shift and erode if left on their own, not a good prospect for the longevity of such a shallow hole. In the somewhat stylized drawing at left, copied from a Louisville Bridge Company stock certificate, we see the railway bridge spanning the Ohio River that was completed in 1870 at about the spot where Holman contemplated placing his tunnel/ditch. The view is aimed downriver, with Louisville on the near bank. Oddly, the Falls of the Ohio, actually a series of gravel riffles that began at the bridge, are not depicted. |

||||||||

Holman must have known something of the Thames Tunnel, given his voracious interest in technology, but his own experiences working on Indiana's canals likely got in the way of thoroughly understanding Brunel's methods. As the ex canal engineer, he was practiced at cutting watercourse ditches through solid ground, but what he did not seem to appreciate was that there is a serious divergency of functions between containing water within a canal and keeping water out of a tunnel. Leakage is acceptable in the former, while it can be the death knell to the latter, as Trevethik found out. Although the approaches were true tunnels, Holman's planned to "tunnel" under the Ohio with a ditch whose roof would lay barely underneath the river bottom. In his eyes, the tunnel was a canal in reverse, and the fall in the river below it could be used to his advantage when erecting cofferdams to divert the flow away from the trenching. What he did not learn from Brunel was how tough it would be to keep water out once the river began flowing over the top. Brunel used iron to line his tunnel, whereas Holman seemed to think that sandstone masonry sealed with a "natural" cement (that he expected to excavate from the ditch) would do the job. Based upon the experiences of others before and since, well, nope. In terms of stimulating a revenue stream, the plan worked pretty well. In his ignorance, Holman certainly viewed of his design as competent - perhaps genius - but the fun question is, did he really intend to dig a tunnel, or was he merely hoping to mine bank accounts, or both? We shall be pondering this question again and again about his future escapades. As part of the grand rollout of his tunnel plans, Holman used his family's political connections to coerce Indiana Governor Joseph A. Wright to travel down to Louisville to pitch the railroad at its potentially most lucrative group of investors outside of the financial markets in the East. On November 16, Holman stood armed with his map before a crowd at the Louisville Merchants Exchange to describe the tunnel's details as Wright's warm-up act. The governor in turn conducted his presentation "in a happy vein of mingled argument and exhortation," according to the Louisville Courier, while in a spectacular case of misjudgment, Louisville Journal opined that, "Mr. Holman is a practical engineer." The crowd was reported to be "large and highly respectable" (meaning big money was present), and Holman maintained that the tunnel would absolutely cost no more than $1.2 million (~$35 million in today's money), yet the oratory only inspired listeners to cough up $1,000 in pocket change towards subscriptions before adjournment. The session kicked-off a more successful campaign that fanned agents all over FW&S territory throughout the winter. It met with moderate success among Louisville heavyweights, although the city itself remained indecisive about support. In December, Louisville Times published a lengthy editorial endorsing the tunnel, which only could have been good news for FW&S stock peddlers, but it immediately generated a series of tunnel-bashing letters under the pseudonym "Bridge" to the rival Journal, which the editor was happy to publish. The Courier also chimed in on the tunnel's behalf, but the extended airing of pro-bridge arguments took some of the sheen off the tunnel. In the new year of 1855 FW&S felt hearty enough to pronounce that a force of 100 men had been put to work grading the road between Bluffton and Fort Wayne, with the expectation of laying rail by May. In the past, the company often advertised that contractors were on site, but workers never managed to get much done. FW&S at one time or another claimed that most of its right-of-way was ready, or soon would be ready for rail, yet postmortems conducted by others found that only the southern third of the line had seen any significant grading. The approach of spring usually fosters an expectation of rebirth and growth, but for FW&S it marked the onset of an irrecoverable death spiral. In late March, the company attempted to float a $240K bond issue in the New York market, but withdrew it after just a few days after it attracted no takers. Holman quickly turned to Louisville with a plea to endorse the bonds so that, he maintained, FW&S could afford rails and materials to commence laying track and finish off the line by late fall. Louisville refused, because by now the city was more interested in supporting two new railroads that intended to connect the city with the south. One of them, Louisville & Nashville, already had a few miles in operation, something Holman's outfit had not managed to do in six years. Holman still had one more, much stronger card to play. In anticipation of becoming a boomtown with FW&S's completion, Jeffersonville's town fathers had speculated heavily in real estate, so when the bond debacle became public and highlighted railroad's tenuous financial position, it threw them into a panic. Holman understood their tight spot, which he abused throughout April to leverage a generous subsidy. The deal was set in principal at the end of the month, and all that remained was signing the documents. On May 8th, the city council invited the railroad directors to a regular council meeting, where a formal vote was held that affirmed the deal. Jeffersonville, a little burg of maybe 2500 souls, would trade $200K (2021: ~$6.7 million) in city bonds for FW&S stock. One measure of the town council's desperation was that they agreed to purchase the $25 shares at full face value when they were selling for $10 on the open market. A more revealing indicator of the extent of their fears was that both the stock purchase and bond sale were illegal under Indiana law, unless they had prior approval from the voters in a formal election. The council knew this, and resoundingly learned after the meeting that many of their constituents did too. The politicians attempted to patch up the ensuing row by holding a mass meeting on the 12th to ratify a resolution validating their actions through a showing of hands, and although Louisville Journal reported that it was overwhelmingly adopted "with only six or eight dissenting voices", this was not the way the state legislature envisioned the election process to work. The meeting only degraded the situation, most of all for Holman. In one of those delectable moments of historical irony, the president of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad (which would come to acquire the southern portion of FW&S under fire sale conditions) now weighed in with a lengthy testimonial of support to Holman on June 13, although he admitted "we [O&M] have our troubles" and lamented that he could not offer tangible aid. The letter finally found publication on June 29 - several days after a group of irate Louisville creditors, who held a significant portion of FW&S's debt, forced Holman out the door. Previously, on the 21st, Holman had been barred from a meeting called by the creditors to replace him as president with one of their own, Abraham Hite. The Louisville junta also demanded a rearrangement of credit on terms more favorable to them. Congressman William H. English - who would be the Democratic U. S. Vice President nominee in 1880, and whose father Elisha was a long term board member - represented the company's interests, and essentially caved-in to their demands. How much the ongoing Jeffersonville affair figured in his removal is unknown, but the main issue of discontent was rumored to be Holman's free spending tendencies...on himself. Years later, Joseph Holman claimed that he had lost $25,000 investing in FW&S. One wonders how this affected his relationship with W.J. |

||||||||

|

At immdiate left is an 1856 Parker-era stock certificate, withas almost always, Secretary Haines's endorsement. Further left is an 1864, unsold bond, presumably issued under Parker's direction By this time, Haines was out as secretary, but he reportedly was a very wealthy man when he died many years later. | |||||||

Further FW&S adventures, sans Holman Although Holman's episode ended with his dismissal, FW&S and Jeffersonville's further adventures are bizarre-enough to deserve a brief telling. Based on his later record, Holman probably was generous in his personal use of company funds, but the real skunk of the organization may have been long time secretary David T. Haines, who co-signed stock and shinplasters with Holman. The creditors showed him the exit, as well, but he arose like a phoenix in October, when an entirely new board was installed. As former secretary, the fellow who kept track of company business, he knew better than anyone else where the money was buried, so the new regime had no real alternative but to bring him back. He fell in with John C. Parker, who replaced Hite as president, and the pair proceeded to take off on a merry ride at the company's expense, during which Parker seems to have outfoxed Haines for control of the company assets. Early on, Parker got fingered for pocketing the sales proceeds of of more than $20K of company owned stock, but this was small change compared to the several million dollars worth of FW&S real estate that he somehow fell into. During Parker's tenure, he undertook a few faux attempts at reviving the railroad, but this was merely to hook new investors. One of them was a wealthy English capitalist who did his level best to steal the assets from Parker, but finally lost out in the late 1860's after a lengthy court battle. Suits, countersuits and foreclosures continued into the early 80's, involving a host of companies and individuals, including 1876 Democratic Presidential nominee Samuel Jones Tilden and future President Benjamin Harrison. When it was all finally sorted out, a Nickel Plate Road predecessor wound up with FW&S's route from Fort Wayne to North Vernon, and Ohio & Mississippi (much later Baltimore & Ohio - see image at bottom) wound up with the balance to Jeffersonville, where Louisville Bridge Company had opened a bridge over the Falls back in 1870. And alas Jeffersonville, poor Jeffersonville. Their bond giveaway to FW&S wound up precipitating a whole series self-inflicted gunshot wounds in the future. The company's rapid collapse during the next few months made it clear that the value of its stock was on the precipice of total worthlessness. So, what could the city council do but compound their error? In January, 1856 it refused to pay out the first round of interest due on the bonds, a paltry $3,000, with an excuse that FW&S had agreed to pay the interest until they completed their line. The railroad was by then thoroughly insolvent, leaving Jeffersonville holding the bag. This made the city a pariah in the bond markets and led to an inevitable lawsuit, whereby bondholders claimed Jeffersonville was responsible for the interest, since it had never disclosed the interest agreement with FW&S to them when they purchased the bonds. Rather than arguing the point, Jeffersonville responded with an inventive defense that now claimed the bond issue was indeed illegal after all, since it had not been ratified by three quarters of the voters in a proper election, and this in turn meant that their bonds did not exist in the eye of the law. The plaintiffs, they argued, could not sue over something that did not exist. Inexplicably, the judge ruled that the the minutes may have been doctored to legalize the bond issue, so it *probably* was illegal and hence, non-extant. The jury found against the bondholders in December, 1858, but this was not the only good news that the town received that month. In exchange for a right-of-way through Jeffersonville, the moribund FW&S relinquished $100,000 of the city's stock indebtedness. President Parker likely parlayed the the land into a significant part of the real estate fortune that he made and lost. The late developments must have left town fathers feeling high on life, for they repudiated the rest of the bonds entirely in January. This move completed the destruction of the town's credit rating, making it more difficult to scrounge up defense funds while the case case wound its way through the appeals process for the next 13 years, only to see the original judgement reversed and the bonds reinstated. Jeffersonville paid off the last of them in 1922. |

||||||||

|

page top

Part 4: The Occasional Sourdough: |

|||||||