More war stories...

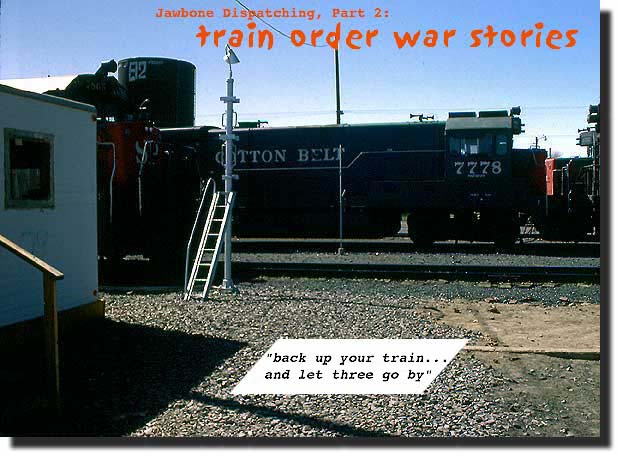

Take another look at the title photo, above. I recorded that shot at Santa Rosa, New Mexico, on one bad day. The trailer functioned as the train order office, and behind it stood three trains, all waiting for the other guy to move. But the actual problem was some 35 miles down the line at Leoncito, where the dispatcher had arranged a dandy Jackpot (an SP term for gridlock).

That day in mid Spring, 1984, I was a brakeman on the far train in the photo (its GP-35 is visible at the right side of the photo), the Santa Rosa work train sitting on the Stock Track. A few days prior, I had been force-assigned (whining like a stuck pig, I might add) to it for a week off of my higher-paying regular job as the rear pool freight brakeman for Sammy Gohlson, a veteran conductor and Tucumcari native . The other two trains were pool jobs, whose crews sat scratching their heads while the drama at Leoncito preoccupied the dispatcher, known by his radio call sign, TD6.

Leoncito on a better day...

Such manner of instructions was a BIG no-no in the tightly regulated world of train orders, and evidently the dispatcher was in dire straits. He had concocted a one-legged meet (see "MEETS" explanation, above) between the extra east and three westbounds. Unfortunately, the only crew that was left ignorant of the situation was on the train that was supposed to be in the siding at Vaugn, west of Leoncito. Apparently the dispatcher was hoping that he could clandestinely straighten-out things without a big blowup that would get him fired.

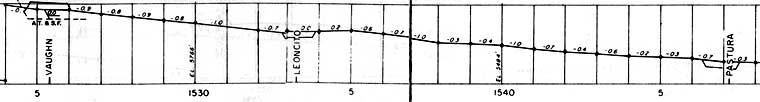

The easy out was not to be, for even if the dispatcher was looking at the following grade profile, it only told part of the story:

Rightfully enough, the engineer communicated this to the panicky dispatcher, and flatly refused to back his train up the grade, lest some of his cars decide to go north and south, rather than west. One westbound had already gone by Pastura when the dispatcher received the engineer's bad news. The only option left to the dispatcher was to call that train and convince them to back up so that the extra east could head into the siding at Pastura and let the others go by. The second (in the photo with the 7778) and third (out of photo) westbounds sat at Santa Rosa, "frogged" by the eastbound (photo foreground) which hung out on the main track west of the siding, and was also stopped at the train order office for lack of orders (I believe that the dispatcher did this intentionaally to cause a roadblock).

All of this took several of hours to straighten out. Whether the dispatcher got the west trains around the east man (train) by radio train order or illegal jawboning I didn't hear.

The extra east wasn't out of the woods yet, though. It's crew was running short of Hours of Service time, and the train only made it as far as Arabella siding, between Pastura and Santa Rosa, before they "went dead" (their time expired). Since we work train guys were sitting on our hands waiting for the railroad to clear up anyway, the powers that be elected to have us "patch" (relieve) the dead crew, and our track gang foreman volunteered to take us up the hill to Arabella.

When we got there, who should be waiting there but my discombobulated regular conductor, Sammy! He looked like he'd been through the proverbial meat grinder and sulked off to the Carryall.

I'm sure that Sammy wasn't half as glum as the dispatcher, who probably went without a paycheck for quite awhile after this episode. Things worked out rather well for we work train guys, however. We took Sammy's train on to Tucumcari, which according to the agreements meant that we would be relieved of the unwanted work train assignment and restored to our regular jobs. It's nice to reside in the silver lining once in awhile.

![]() For another tale about the Santa Rosa work train, train orders and good fortune, see our story about the Work Extra 6353, part of our Train Order Primer final exam.

For another tale about the Santa Rosa work train, train orders and good fortune, see our story about the Work Extra 6353, part of our Train Order Primer final exam.

When departing Tucumcari or Carrizozo, the wise railroader always carried a couple of "thousand milers" (large sandwiches) and an assortment of other consumables to keep up his blood sugar for the duration of what could become a very long day. There was no guarantee that even a hotshot could get you over the subdivision in the Federally-alloted twelve hours, so it was best to come to work fully prepared.

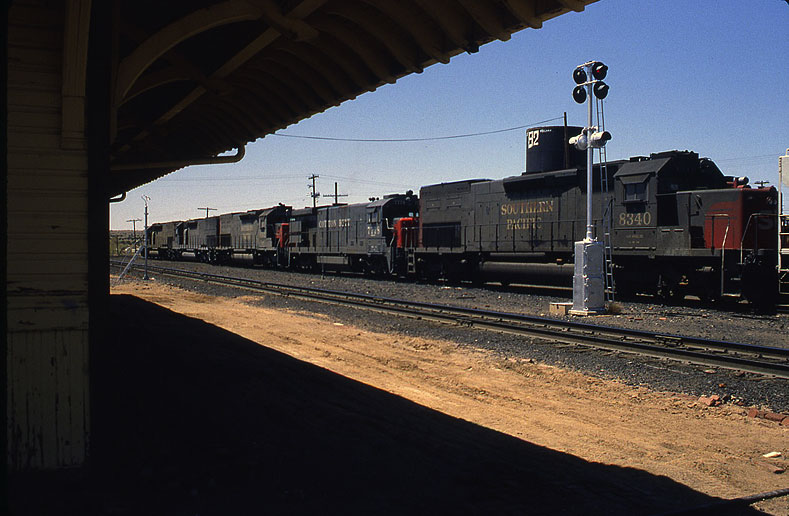

Unless you are strong enough to carry around a supermarket, there's no way that you can fully provision yourself for the worst-case scenario. Thus, I'm still amazed that I had enough energy to snap off the above photo, because, at that particular moment, I had gone without anything to eat for a long, long time. Yep, I had supplied myself with thousand milers - it's just that I had finished off the last one about twelve hours previously. You see, the above train on the right is heading into Leoncito siding with a relif crew crew for our relief crew. When they finally climbed aboard, things got pretty crowded.

I can't recall the particulars of why out train fell down so badly - perhaps temporary malnutrition wiped out some memory cells. It may have been the day that the Track Department was breaking-in their new laser track aligner up above Ancho somewhere. They truly broke it in and broke an axle in the process. My train was on the wrong side of the predicament, and after we waited for six hours for them to drag it into a spur, the chief dispatcher down in Tucson had had enough and ordered the $1.2 million (in 1984 dollars) machine bulldozed off of the rails - on its side into a ditch, as it turned out.

Regardless, I was stuck on a lowly dog train (as evidenced by the SD-9 in the photo - the only one that I saw during my six months stay in Tucumcari) that departed Carrizozo before dawn. Dog trains fared poorly under the best of circumstances: once you got delayed, you only got even more delayed later. A significant hold up in the beginning led to bad meets, and the inevitably to a wait for a dreaded track work window. If we had been on the United Parcel Service hotshot, the chief dipatcher would have ordered the track gangs to clear up and let us by, but alas, we were not.

We managed to make it as far as Leoncito that afternoon, during a typical New Mexico Summer gullywasher, and it was still pouring when our relief crew arrived after sunset, several hours after we had died on the law. The new crew managed to move us a few more miles to the next siding, Pastura, before Hours of Service caught them. They had come via train out of Tucumcari, because the rain was so bad that much of the line was inaccesible by company Carryall, and their "ride" had experienced unanticipated delays. Thus, they already stood woefully short on time when they swung aboard our equipment. The second relief crew, that arrived via train after my crew's second sunrise, had several hours against them as well, but the twelve of us had no trouble making Tucumcari, because the dispatcher held up the entire railroad ahead of us so that he wouldn't have to call crew number four - 20 percent of Tucumcari's chain gang (pool freight crews) would then have been squeezed aboard this one God-forsaken train...

Altogether, my crew endured 28 hours on the train, a personal record that I never bested, thankfully. The upside was that I made so much money on this trip that I had to use the "big calculator" (RR slang for a calculator with lots of digits) to compute my earninings, even if it was "blood money".

Despite the mayhem that was The Sub in 1984, luck often smiled upon me, and on a few rare occasions, it gave me a big, broad 'Howdy!'

By mid-April, crew shortages became so acute that SP was forced to go prospecting for bodies elsewhere on the system to keep the trains moving (and, on one or two occasions about this time, SP deadheaded people via helecopter). In particular, SP found two good ol' boys down in Ennis, Texas on the T&L and flew them up to Tucumcari. For this intial effort, they each received a 1252 mile deadhead (to the uninitiated: that's 12.5 days' pay, folks!), and of course, complementary peanuts from the airline.

That night, these two brakemen must have had big, happy smirks on their faces when they swung aboard Conductor Don Nash's westbound out of Tucumcari, but their luck soon changed. Twenty-seven miles down the line, the siding at Simmons (see below) sits abreast a low hill. The steepest part of the seven mile grade is in the middle, where three miles of one percent bested the train's asthmatic power. The Ennis boys had to get down off of their perches, tie hand brakes, cut the train in two, and double it up to Simmons. We've already discussed how much brakemen enjoy doing this.

Possibly the power of prayer prevailed, because the train managed to squeak up the next long pull, but that ended on the grade through Arabella, when one of the units caught fire, bringing things to a halt once more. Again, they doubled the hill, and eventually died at Vaugn, although I'm not sure how much of the train accompanied them that far.

After dragging into Carrizozo in the company bus (a.k.a.: carryall), the two fellows decided that they'd already had enough, laid-off and headed for Ennis on the Greyhound, eating their 1252 mile return deadhead in the process. In all, luck had nevertheless smiled upon them - roughly fifteen days' pay is pretty good compensation for one bad night on the railroad.

Now fortune altered its gaze towards me and another Ennis man, a fellow named Aycock. Down in Carrizozo, Don Nash again was sans brakemen, so that evening Aycock and I happily slept our way to the rescue in a carryall driven by a clerk who was none too pleased to be making a 350 mile round trip drive in the middle of the night.

We hit town around 1:00 a.m., and by mid-morning had a call for the return trip - a deadhead! Well 'Howdy' back at ya, Luck!

Westbound sitting in the hole waiting for two east men; sunrise, Simmons, New Mexico, mid-1984

Dateline 2013 - Long Lost Photo: The above shot showing a typical extra west in the hole at Santa Rosa's train order signal remained forgotten and misfiled for 29 years; unused in the production of this page in 2006. Better late than never.

Since the situation on the Carrizozo Sub was so desperate by 1984, something had to change. Reconstruction and operation of the line was literally breaking Southern Pacific's financial back.

So, as a first step in the Spring of that year, Number One Market ordered Western Region General Manager Rollin Bredenberg to go down and clean-up the mess. That, he did.